Impact Guest Blog: Becky Milne, Professor of Forensic Psychology, writes this long-form post on her routes into impact and finding her golden thread.

School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, HSS

The start: my motivation

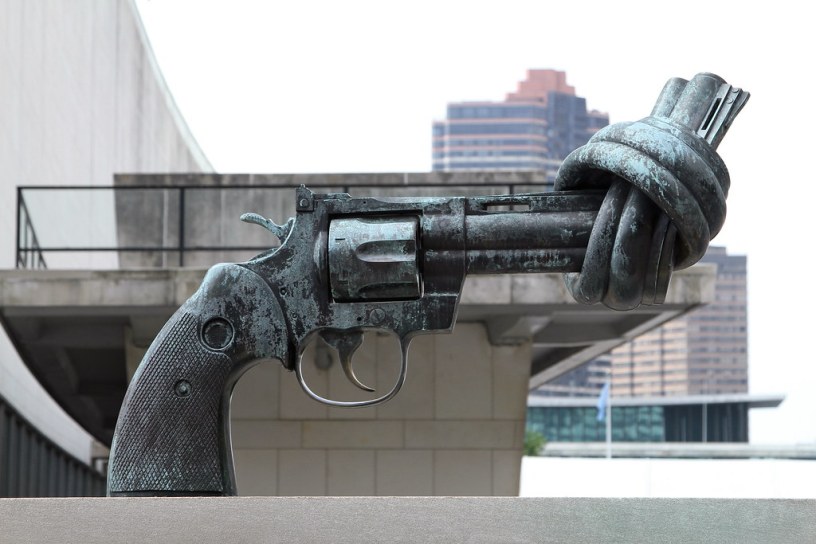

As a fifteen-year-old I had a family holiday to New York. While we enjoyed the usual tourist traps, Empire State et al, my parents took me to what was the most impactive place that set me on my path – The United Nations Building. As a women’s activist, my mother always taught me to question everything, and from then on, I entered the world of social justice. Fast forward near on forty years and I have just been asked by the Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhumane, or Degrading Treatment of Punishment, to give opening remarks to a select committee of experts on investigating crimes of sexual torture committed during war and armed conflict as part of her preparations for a thematic report to be presented to the UN General Assembly. So how did I carve my impact path? Keeping the momentum, where resilience is key to a successful Impact Case Study.

I wanted to be an optician, but luckily my A levels did not go as planned, so came instead to Portsmouth to study psychology, where I met my mentor, my UG dissertation supervisor, who to this day I call PhD Dad. One crucial element to forging an academic career including developing a research and impact strategy is having solid mentors: people you can throw ideas at, vent at, a stalwart in your life. ‘Doing’ research and impact is never smooth sailing. There are always turbulent waters to be navigated, and a mentor can help choose the right path and provide that map when needed.

My research identity is…

“as a global expert on the application of psychological theory concerning memory and communication to the practical environment of criminal justice. Her research in forensic psychology draws on multiple disciplines within psychological science, including the cognitive psychology of memory and the social psychology of interpersonal communication” (ICS, 2021).

What does identity really mean? PhD programmes of research make one be an expert in a narrowly focussed area (mine forensic interviewing of vulnerable groups), and this is where most of our research worlds start. Then we have to broaden and spread our wings but not too far lest we lose our identity. This balancing act of being known for ‘something’ to broadening one’s horizons, grabbing those opportunities is hard to manage. Within the academic world there are tangible ways to be associated with a certain area of expertise. Over time, growing numbers of publications, grant funding, and successful PhD students can all help develop one’s academic esteem.

Impact however, is another ball game. Trust is central to harnessing support and relationships with those who should be benefitting from the product of our research labour. Developing trust takes time and patience. ‘To be the go to person’ is what is often said when writing ICS – how can you evidence that? This is not easy, less tangible, but not insurmountable.

Finding the gap

The golden thread of my work stems from giving everyone access to justice – giving everyone a voice. From the early work of how best to enable children to give reliable evidence to fuel investigations into crimes committed against them, to the most recent work of trauma informed interviewing of victims of war crimes. Finding the gap in societal needs, at that moment in time, where your skills/research base could be useful is important to the story that underpins an ICS. Leading up to the 2021 ICS society had seen an increase in terror attacks. In such situations casualty/witness interviewing is complex because of the confusion and chaos surrounding the event, limited fast-time resources, the memory of witnesses decaying over-time (with potential contamination by external sources i.e. the media), and the scale of the problem (approximately 8000 witnesses in the London attacks). In addition, gaining reliable information from witnesses to inform the emergency services whilst taking heed of their trauma is a difficult task and can be compromised by poor interviewing, or greatly enhanced with sensitive interviewing. Getting it wrong however, has far-reaching costs to society, not only psychologically but also economically. Getting it right is crucial in ensuring a safe and resilient society. There was a gap.

Attaining the impact and evidence

Based on my long-standing expertise in the field of forensic interviewing (e.g. being member of National committees, having past students being practitioners in this field, being an expert witness, and advising on real cases such as Sarah Everard, i.e. developing real-world practitioner networks, trust, and showing your utility) and working with vulnerable people in jeopardy, I jointly (with the police) created a triage framework for deploying police resources most effectively to engage with witnesses. My peer-reviewed research that looked at how best to garner reliable information from traumatised individuals led directly into informing practical advice in the response to the London Bridge terror attack. This has resulted in national policy and practice change and the framework is now used in every terror attack in the UK, and in turn results in a better service for those having to recount such events – giving them a voice. By working collaboratively with the end-user practitioners themselves to shape the research, my work has impact that has depth and reach (now used in countries such as the Netherlands, Ireland, France).

The next steps: always looking towards the next gap

Most prior research in investigative interviewing has stemmed from laboratory-based experimental studies concerning the best ways to access reliable information in controlled settings. My field work has added to this evidence-base by addressing previously-disregarded dimensions: the need to manage the ‘trauma’ of victims in their own long-term best interests, and the need for particular skills amongst interviewers to do this successfully, while extracting valuable evidence and information for the investigative process. Together, these add up to a new model of ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ for the management of such interactions. War seems to be everywhere at the moment, and so unfortunately there is a gap. I have been working with the UN for the past few years and the next stage is helping those to empower victims of war crimes, including sexual violence, that tends to be committed against women. My mum would have been proud – I am still fighting the fight for justice.